High Level Practice Framework

Level 5 - Golden Bear

Tl;dr

Practice is more about getting the brain to accept swing changes will lead to good results, than it is about building muscle memory. Quality practice is made up of clear intent, focus, and developing mind-body connection. The body is intelligent; the best way to practice is setting up conditions where your body can unconsciously learn how to perform to get your desired result. Swing changes are made through mind-body connection/awareness, isolating the new pattern, scaling up the level of variation in your practice, then learning how to take it to the course.

Practice and preparation are how you get better at anything. How well you practice determines how fast you improve. Good practice habits aren’t taught by golf instructors, allowing them to keep getting paid for lessons.

As with anything, it’s not only what you do during practice, but also the manner you go about them. Good practice is not just about going through the motions. True focus and intent can cause huge improvements in a very short amount of time.

My practice philosophy is different than the traditional perspective. I want to practice in a way I can get better even if I’m not executing what I’m consciously trying to. The goal of practice is to set up conditions that allow your body to learn how to create the motions that create the shots you want. I want to get better without trying.

The Barbell Approach: Block and Random

The Barbell Strategy is an investing concept where someone invests in high-risk assets and risk-free assets, while avoiding medium risk assets. It’s a way of being conservative and aggressive at the same time, which changes the nature of the payoff. It caps the downside while maintaining the upside.

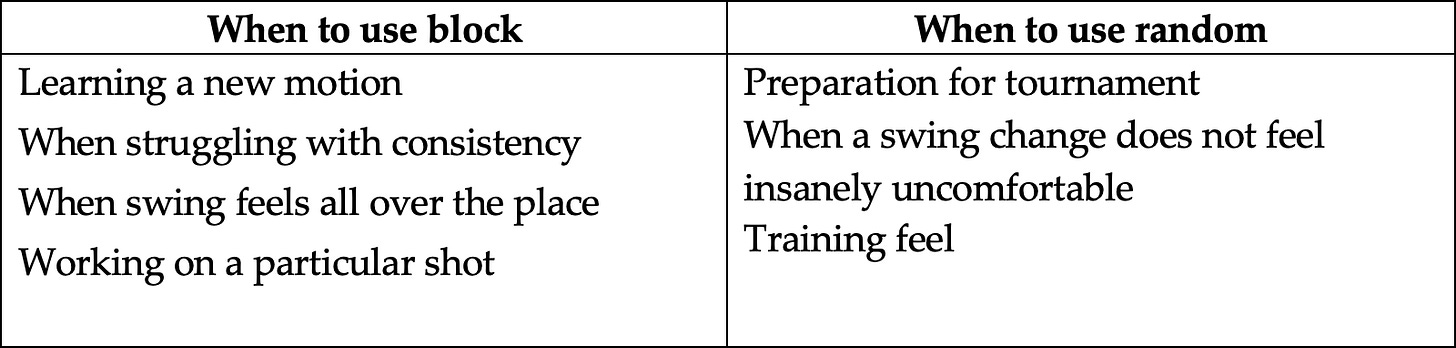

Similarly, there are two commonly accepted ways of practicing: block and random. Block practice is doing the same thing repeatedly – e.g., hitting 10 shots at the same target. Random practice is varying repetitions, so the same thing is never done twice in a row – hitting 10 shots with 10 different clubs with different trajectories.

Both ways of practice are useful. Block practice is great when trying to learn a new motion or a new technique. However, block is not great for transferring a new motion to the course (it’s also boring). Random practice is much better for transferring a skill to the course, as well as refining a skill or motion. On the other hand, it can be much more frustrating than block practice, and it’s not the best for learning something brand new.

There are strong advocates of both methods. Scott Fawcett, the notable golf strategist, strongly advocates for block practice. Hank Haney, Tiger’s old coach, taught Tiger to use 9 different shot shapes when practicing. It’s wrong to argue which method is better, they’re useful in different ways for different purposes.

The problem I see is most people, high level players and high handicaps, get stuck in the middle of the two and miss out on most of the benefits of either method. They’re hitting the same club over and over with no target in mind, trying out different swing changes every few shots, purposely hitting shots with crazy trajectories, etc. When practice is done without intent, it’s not practice, it’s exercise. Consequently, the body doesn’t adapt in a productive way, and low rates of improvement occur.

Instead, practice should be hyper-block or hyper-random. If a player is learning a new swing change, they should be hitting 50 shots to the same target while consciously focusing on the new movement pattern. If a player has a tournament coming up and wants to refine their ballstriking, they should be varying target, club and shape on every shot while going through their full routine. If a player is struggling with their bunker game, they should spend an hour hitting nothing but standard bunker shots. If a player wants to tighten up their short game, they should be throwing balls all around the green at random and try to get as many up-and-down as possible.

Block practice when learning something new, random to build/refine a skill or change.

Caveat: there is such a thing as too much randomness. The brain is a pattern-recognition machine. If you tax the body with new patterns beyond the brain’s capacity to recognize, there’s no positive adaptation. Block practice is useful in the beginning of a new motion pattern; the brain/body gets a chance to recognize the new pattern by doing it over and over again in exactly the same way.

Once a new pattern becomes established, adding variation to practice is beneficial. However, too much becomes toxic and a detriment to your game.

I’d also argue varying how random your practice sessions are is beneficial. Doing a session of block practice, emphasizing a particular swing change by hitting balls solely focusing on the change, and the day after, simulating a round of golf on the range, is certainly not going to hurt.

This is a good way to maintain balance between block and random practice while still extracting the full benefits of each method.

Presence

No matter what you do when you practice, the manner in which you go about it is just as important. Presence and focus are the two factors behind rapid improvement. What do I mean by presence? It’s the quality of being fully immersed in the task at hand. In sport, this is manifested in the athlete putting all focus into the body.

For example, let’s say someone is deadlifting while their mind occupied on something else. It could be the music one playing, what they’re doing later that day, etc. Another person is deadlifting while the mind is fully into the lift. They feel the muscles in the posterior chain contract, the feet pushing into the ground, and the core actively stabilizing. The second person is developing mind-body connection, a heightened conscious awareness of how the body is functioning. The second person will be far better at having the proper muscles firing as well as spotting technical issues. Over time, this leads to greater strength gains and fewer injuries.

Awareness practices like meditation restructure white matter in the brain. White matter is made up of myelin, the fatty substance around axons that allow electrical impulses in the brain to travel faster and more efficiently. Practicing with heightened awareness quite literally rewires the brain.

“How do I apply this to golf?”

There are two ways: practice in large, uninterrupted blocks of time, and “go into the body” on every rep.

Uninterrupted blocks of time create the conditions for deep concentration, leading to greater ROI for each rep. The problem with large time blocks is not everyone can free up enough time; I’ve found it takes at least an hour to switch into deep concentration mode. The other problem is, it is difficult and can be boring. Practicing without breaks or conversation can suck the enjoyment out of it. It’s also mentally taxing. Long periods of deep concentration burn a ton of calories, leading to a feeling of exhaustion afterwards.

Going into the body on every rep are like bite-sized quantities of deep concentration. Whether hitting balls, doing putting drills, or playing games, placing conscious awareness on how the body and the club are moving aids in developing mind-body connection.

This means doing things such as taking slow, intentional practice swings before full shots, trying to really feel the putter-head while doing lag drills, or feeling the influence of grass on pitch shots out of the rough. The point is to place as much awareness as you can into the body or the club. There are a couple of benefits of this. If you’re working on something technical, placing full awareness into the body parts involved in the new motion pattern helps develop the new “feel”. The new “feel” becomes easier to recognize, enabling comfort with the new motion at a faster rate. If skill development is the focus, full awareness allows the body to learn how to create the shots desired, without the aid of conscious technical changes. This is how feel and touch are developed.

Long term, this leads to insane levels of hand-eye-coordination. Tiger Woods can sense something off in the downswing, right before the club explodes into the ball at 120+ mph and make a compensatory adjustment. This isn’t something you can practice, it is the body itself recognizing important factors throughout the swing (club face, body position, hand position, etc.), spotting the issue, and making an adjustment, all in under 0.1 seconds. Although this is an unconscious process, conscious awareness throughout the swing helps with developing this skill.

This doesn’t require you to be in a deep work session. This works whether you’re warming up for a $5 Nassau or in your 7th hour of practice.

Caveat: On the course, I wouldn’t quite recommend this level of bodily awareness. I would of course advocate for being as present and into the shot as possible, but the best way to play well is being reactionary to the target.

Swing Changes

Like it or not, a golf swing is the most technically complicated action in sports. It’s amazing the human body can execute the type of precision a golf swing requires. A one-degree difference in face angle can be the difference between winning a major or coming up short.

As far as technique, I don’t know what your swing needs. That’s up to you, your knowledge, and whoever is coaching you. I can help with implementation. Swing changes can occur much quicker than common thought would suggest, if done correctly.

This is the basic framework:

Isolate

Slowly Integrate

Refine by Randomizing

Take it to the Course

As always, take videos throughout this process to monitor progress.

*Also helps with adjusting the level of exaggeration you need to execute the positions you want. The more you practice, the more natural changes feel over time. *

ISOLATE

When introducing a pattern the body is unfamiliar with, it can be very difficult to hit a golf ball at full blast. A full golf swing takes less than 2 seconds to complete (unless your name is Hideki Matsuyama) and can be 120+ miles an hour. When you do something different, especially in the downswing, the brain must figure out a way to hit the ball solidly while in a position the body does not recognize. All sorts of compensations have to occur to accomplish this task, and results in very inconsistent strikes.

Instead, isolate the portion of the swing you’re working on. Musicians learn by breaking a piece of music into small chunks, practicing each small chunk until they become automatic, then integrating everything into the whole piece. The same method works with athletic skills.

Pump Drills

If you’re working on the takeaway, a good way to start off is by setting up to the golf ball, taking it to the end of the takeaway (about waist height with the club), bringing the club back to the ball, then repeating 2 more times. After the third “pump”, make a three-quarter swing or full swing.

The isolation takes place in each “pump”, where the focus is solely on the part of the swing you’re trying to alter. Piecing this into a partial swing helps the movement feel more natural over time. Pump drills are very effective at changes in the downswing or transition.

A variation of pump drills is pause drills, where you complete a swing up to the part you are working on, pause for a second or two, then complete the shot. This is useful for working on the transition between backswing and downswing.

Partial Movements

Half and three-swings can help tremendously, and effective for almost every change you could think of. Whether it’s weight transfer, swing plane, impact conditions, etc. It can even work for top of backswing changes, as long as it’s paired with a three quarter follow through.

Here’s a fantastic video of Ben Hogan teaching the golf swing by gradually increasing its length:

SLOWLY INTEGRATE

After the new movement becomes comfortable in shortened swings, it’s time to integrate it into full ones. It’s possible to go straight to full speed swings, but it doesn’t quite get the job done. It’s very effective to make full motions in slow motion. This helps strengthen the mind-body connection through forcing you to feel the motion and how the change integrates.

Hank Haney, Tiger’s old coach, encouraged Tiger to practice in super slow motion when he was coming back from his 2008 knee surgery. Tiger would practice hitting Drivers 50 yards, then 100, 150 and so on. I’ll let Hank speak for himself.

“The exercise had a lot of benefits. Because he was swinging so slowly, Tiger avoided favoring the injury and getting into bad habits. The slow swing with the longer clubs also made him more conscious of correct technique and really ingrained the moves we were working on, just as had occurred when Tiger had filmed the Nike commercial in slow motion, but to a much greater extent. As far as he knew, he was the only player who’d ever used such a program to come back. It was different and special, and he always thought that gave him an edge”.

*Hank Haney, The Big Miss. Page 182, Crown Publishing Group, 2012.

Take Hank’s advice and start hitting shots at very low pace and speed, then gradually increase until full. Also, I highly recommend taking 2 or 3 slow motion practice swings before hitting each shot on the range. It helps place awareness on what you’re working on and keeps you focused throughout a practice session. If it works for you, do this on the course as well.

REFINE BY RANDOMIZING

Once a change reaches the level of comfort where it is relatively easy to do on a standard shot on the range, it’s time to take it to the next level. To force adaptation, we need to increase the level of complexity to an appropriate level. We can do this a multitude of different ways, but it all involves varying some part of the practice.

The first way would be varying the club selection from shot to shot. It can start off by hitting 3 shots with one club, then 3 shots with a very different club (e.g., 1st club being a wedge, second being a long iron), and then continuing. Hit standard shots. Remember to take practice swings before each shot and to put your attention on the motion you want to execute. Once this starts feeling comfortable and the quality of shots is high, reduce it to varying the club every other shot.

When you feel comfortable with the new motion in this process, we can now attempt to vary trajectory and shape. Start with a single club and single shot. For example, start with a 7 iron, hitting only draws for 10 shots. Then, change clubs and change shots; let’s say switching to a 5 iron and hitting fades. When this feels comfortable, start varying the height, e.g., high shots with an 8-iron for 10 reps. Then, vary the type of shot with a single club.

We can then start combining things, starting by varying height and shape every other shot with a single club. For example, we could hit different shots with one club for three shots, then switching to a different one. Finally, we can vary the club and shot every other rep. If the change feels comfortable while doing all of this, we are well on our way to it being ingrained forever.

The reason we want to vary clubs and shots while focusing on the new motion is to make sure it transfers to the golf course. The course can force you into all sorts of situations: crazy lies, elevation changes, swirling winds, etc. When these new circumstances arise, the body defaults back to old habits in attempt to exert some sort of control and familiarity. It’s actually a very intelligent thing to do because we typically haven’t reached high enough proficiency with a swing change to warrant its use in new situations. Ideally, we want to get to the point where the body is comfortable enough to apply this new “skill” to new situations.

When we vary our shots and clubs, and scale up randomness in an intelligent way, the body goes “If I need to hit this shot, this new unfamiliar movement still allows me to hit the shot I need, so I’ll use it.”

TAKE IT TO THE COURSE

Even after all of this, your swing on the range can look different than your swing on the course. There have been countless times where a video of my swing on the range looks perfect, then a video of my swing on the course looks terrible, despite feeling the same thing. It is a part of the game that applies to everyone, even the best of all time.

This of course, doesn’t mean it can’t be done. I believe it can be done quickly if we are smart about it. The same process for refining a change on the range is effective for the course.

I suspect you’ll play rounds while going through this integration process in practice sessions. During this time, when on the course, go through slow, intentional practice swings before every shot. Then, as always, be aware of the new motion and how your body is moving during actual golf shots. Unfortunately, shot quality won’t be as good as we’d hope because the body isn’t accustomed to this new pattern in on course situations. If you’re playing in some sort of competition, I’d recommend leaving this for the range. Otherwise, this as an important step that pays dividends over time.

When we get to the point on the range where we are comfortable hitting all sorts of golf shots with the new motion, we can start going hard at getting this to stick. During the first round or first couple of rounds, I’d recommend hitting nothing but standard golf shots. Of course, really work on feeling the new change and checking swing videos to see if you’re executing. No two shots on the course will be alike, different lies and stances and distances, so at this stage it is smart to limit shotmaking to standard golf shots.

Once we have this down, we can start varying trajectories in a small way. Hit tiny draws or tiny fades, a couple of low one’s here and there, and take some speed off from time to time. This is the same framework we used from the range. Check video to make sure your swing is up to your liking. Ideally this only takes a round or two.

After that, play how you would normally play while still feeling the new motion. It takes a couple more rounds for the change to be truly integrated. We are of course training the muscles, but the main purpose of this is to convince the brain that it is ok and beneficial to do this new thing for the foreseeable future.

Once in a while after this, check up on the change you worked on to make sure your swing hasn’t gone back to its old ways. If it has, it should only take one or two range sessions and a couple rounds of golf for your swing to be back where it should.

The 10,000 hour rule is a farce. If done correctly, swing changes can be fully integrated in 1-2 months.

Practeenis